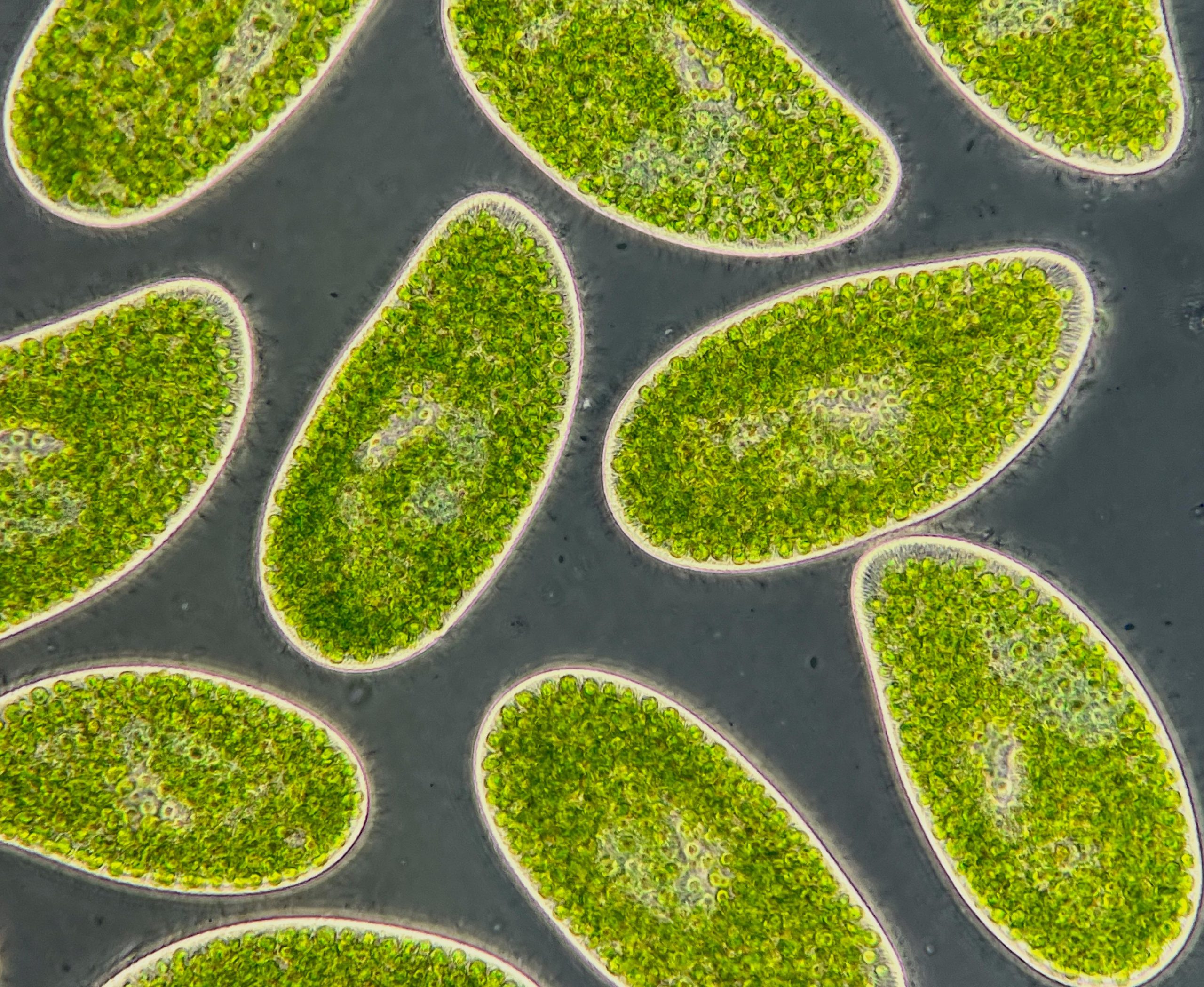

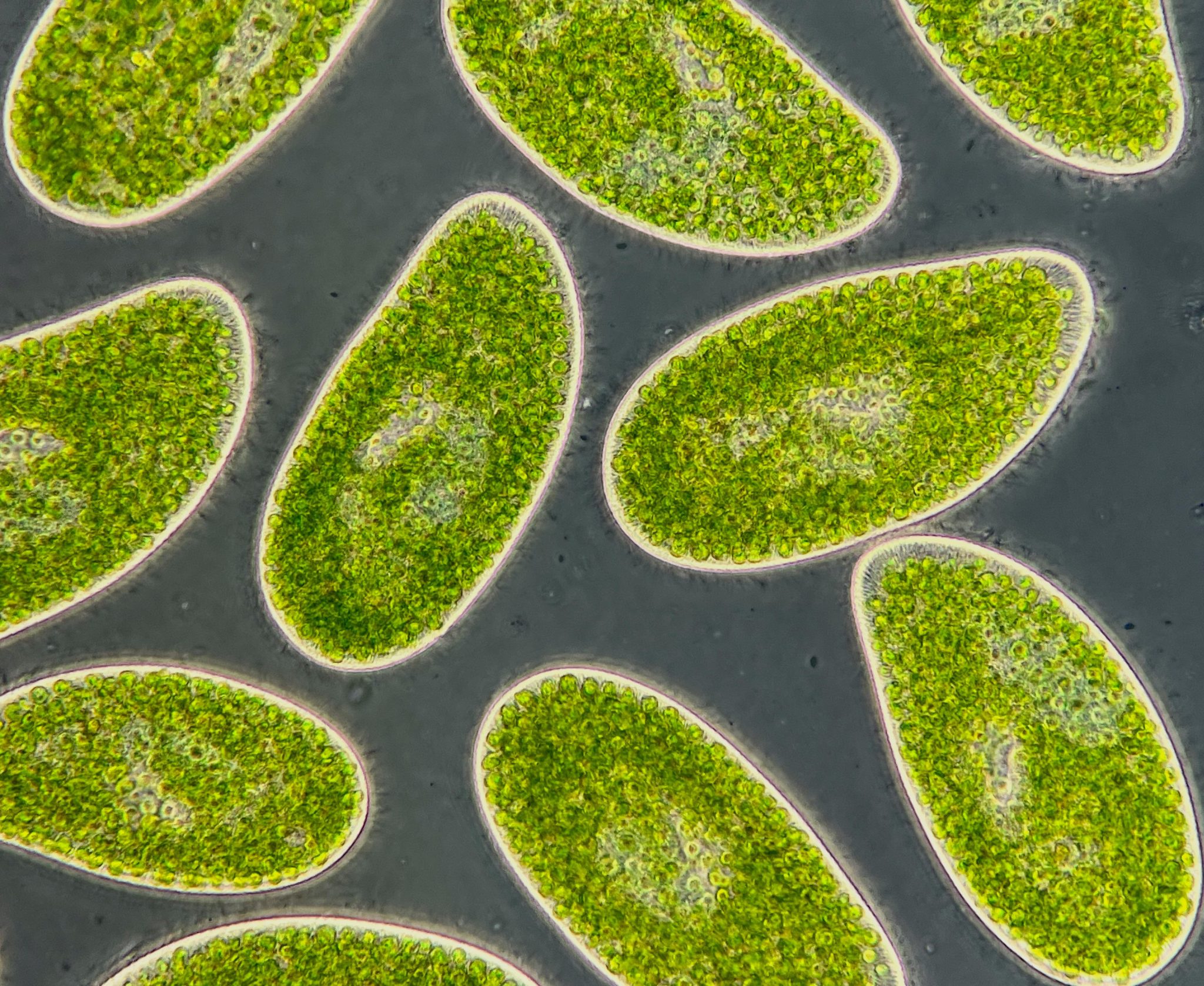

Takéto jednobunkové organizmy sa nachádzajú v jazerách a riekach po celom svete Paramecium bursaria Obaja môžu jesť a vykonávať fotosyntézu. Takéto mikróby hrajú dvojakú úlohu pri zmene klímy, uvoľňujú alebo absorbujú oxid uhličitý – skleníkový plyn zachytávajúci teplo, ktorý je primárnou hnacou silou otepľovania – v závislosti od toho, či si osvoja životný štýl podobný zvieratám alebo rastlinám. nie. Kredity: Daniel J. Wieczynski, Duke University

Zvýšené úrovne tepla by mohli priviesť morský planktón a iné jednobunkové organizmy k uhlíkovému prahu, čo by mohlo zhoršiť globálne otepľovanie. Nedávne štúdie však naznačujú, že môže byť možné identifikovať včasné varovné signály skôr, ako tieto organizmy dosiahnu kritický bod.

Skupina vedcov, ktorí skúmajú rozšírenú, ale často prehliadanú triedu mikróbov, objavila slučku spätnej väzby podnebia, ktorá by mohla urýchliť globálne otepľovanie. Zistenie však prichádza so strieborným okrajom: Môže to byť aj signál včasného varovania.

Vedci z Duke University a University of California v Santa Barbare pomocou počítačovej simulácie preukázali, že významná časť globálneho oceánskeho planktónu spolu s mnohými jednobunkovými organizmami žijúcimi v jazerách, rašeliniskách a iných ekosystémoch sa blíži k bodu zlomu. dosah. Tu namiesto pohlcovania oxidu uhličitého začnú robiť pravý opak. Táto zmena je výsledkom spôsobu, akým ich metabolizmus reaguje na otepľovanie.

Pretože oxid uhličitý je skleníkový plyn, môže to ďalej zvyšovať teploty – pozitívna spätná väzba, ktorá môže viesť k rýchlej zmene, kde má malé otepľovanie veľký vplyv.

Ale pozorným sledovaním množstva týchto organizmov môžeme byť schopní predpovedať bod zlomu skôr, ako sa sem dostane, uvádzajú výskumníci v štúdii publikovanej 1. júna v časopise Nature. funkčná ekológia,

V novej štúdii sa výskumníci zamerali na skupinu drobných organizmov nazývaných mixotrofy, ktoré sú tak pomenované, pretože kombinujú dva spôsoby metabolizmu: môžu fotosyntetizovať ako rastlina alebo loviť potravu ako zviera. Možno, v závislosti od podmienok.

„Sú ako[{“ attribute=““>Venus fly traps of the microbial world,” said first author Daniel Wieczynski, a postdoctoral associate at Duke.

During photosynthesis, they soak up carbon dioxide, a heat-trapping greenhouse gas. And when they eat, they release carbon dioxide. These versatile organisms aren’t considered in most models of global warming, yet they play an important role in regulating climate, said senior author Jean P. Gibert of Duke.

Most of the plankton in the ocean — things like diatoms, dinoflagellates — are mixotrophs. They’re also common in lakes, peatlands, in damp soils, and beneath fallen leaves.

“If you were to go to the nearest pond or lake and scoop a cup of water and put it under a microscope, you’d likely find thousands or even millions of mixotrophic microbes swimming around,” Wieczynski said.

“Because mixotrophs can both capture and emit carbon dioxide, they’re like ‘switches’ that could either help reduce climate change or make it worse,” said co-author Holly Moeller, an assistant professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

To understand how these impacts might scale up, the researchers developed a mathematical model to predict how mixotrophs might shift between different modes of metabolism as the climate continues to warm.

The researchers ran their models using a 4-degree span of temperatures, from 19 to 23 degrees Celsius (66-73 degrees Fahrenheit). Global temperatures are likely to surge 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels within the next five years, and are on pace to breach 2 to 4 degrees before the end of this century.

The analysis showed that the warmer it gets, the more mixotrophs rely on eating food rather than making their own via photosynthesis. As they do, they shift the balance between carbon in and carbon out.

The models suggest that, eventually, we could see these microbes reach a tipping point — a threshold beyond which they suddenly flip from carbon sink to carbon source, having a net warming effect instead of a cooling one.

This tipping point is hard to undo. Once they cross that threshold, it would take significant cooling — more than one degree Celsius — to restore their cooling effects, the findings suggest.

But it’s not all bad news, the researchers said. Their results also suggest that it may be possible to spot these shifts in advance, if we watch out for changes in mixotroph abundance over time.

“Right before a tipping point, their abundances suddenly start to fluctuate wildly,” Wieczynski said. “If you went out in nature and you saw a sudden change from relatively steady abundances to rapid fluctuations, you would know it’s coming.”

Whether the early warning signal is detectable, however, may depend on another key factor revealed by the study: nutrient pollution.

Discharges from wastewater treatment facilities and runoff from farms and lawns laced with chemical fertilizers and animal waste can send nutrients like nitrate and phosphate into lakes and streams and coastal waters.

When Wieczynski and his colleagues included higher amounts of such nutrients in their models, they found that the range of temperatures over which the telltale fluctuations occur starts to shrink until eventually the signal disappears and the tipping point arrives with no apparent warning.

The predictions of the model still need to be verified with real-world observations, but they “highlight the value of investing in early detection,” Moeller said.

“Tipping points can be short-lived, and thus hard to catch,” Gibert said. “This paper provides us with a search image, something to look out for, and makes those tipping points — as fleeting as they may be — more likely to be found.”

Reference: “Mixotrophic microbes create carbon tipping points under warming” by Daniel J. Wieczynski, Holly V. Moeller and Jean P. Gibert, 31 May 2023, Functional Ecology.

DOI: 10.1111/1365-2435.14350

The study was funded by the Simons Foundation, the National Science Foundation, and the U.S. Department of Energy.

Web nerd. Extreme organizer. Writer. Whole foods evangelist. Certified introvert.